Feast of Saint Isaac Jogues, Saint John de Brebuef, and Companions – Option 2 – October 19th

If we read carefully the history of the Paris Foreign Missions Society, one of the great Catholic missionary organizations of the past three centuries, we find a ritual, a departure ceremony for priests leaving for their assignments in foreign lands, that is at once haunting and strangely beautiful.[1]

On the night before or even the very night when the new missionaries were to depart for their missions, they would all gather in the seminary chapel with their family, friends, and fellow seminarians. It would be their last opportunity to pray night prayer all together. Afterwards, an experienced missionary who had recently returned from the missions would give them a brief exhortation, encouraging them to be faithful to God and to their vocations. When he had finished, the missionaries would climb the steps to the altar and, standing in front of the tabernacle, they would turn and face the congregation. Then, slowly, starting with the other seminarians and then family and friends, one by one, those gathered would climb the steps to the altar and, kneeling down, would kiss the feet of the missionaries. Only God knows how many of these missionaries received that veneration of their feet, something similar to the veneration of hands we have after each ordination; for some, it would be the proto-veneration of their relics, the foretaste of the kiss of victory.

The reason for this particular veneration can be found in the anthem that the choir would sing during the ceremony: Quam speciosi pedes evangelizantium pacem, evangelizantium bona! How beautiful are the feet of them that preach the gospel of peace,

of them that bring glad tidings!

The phrase is adapted from Saint Paul’s letter to the Romans (10:13-15), in a passage where he explains the need for missionaries in the first place; he writes: “‘Everyone who calls on the name of the Lord will be saved.’ But how can they call on Him in whom they have not believed? And how can they believe in Him of whom they have not heard? And how can they hear without someone to preach? And how can people preach unless they are sent? As it is written, ‘How beautiful are the feet of those who bring [the] good news!’” God, who calls the missionary in the first place, by that very call sets off a chain reaction: He sends the missionary, who preaches so people can hear and believe and thus call on the Lord’s name and be saved. How blessed is the one that God calls to such a task!

As Saint Paul points out, though, that phrase isn’t an original idea; he’s quoting the prophet Isaiah (52:7). This, then, is an old truth, and one that is worth meditating upon: how beautiful it is to be a missionary! How beautiful is the missionary vocation! As we celebrate the feast of those great missionaries, Isaac Jogues, John de Brebuef, and companions, we can consider just that simple phrase, How beautiful are the feet of those who bring [the] good news, broken down into three parts, and discover, or rediscover, the beauty of our own vocations.

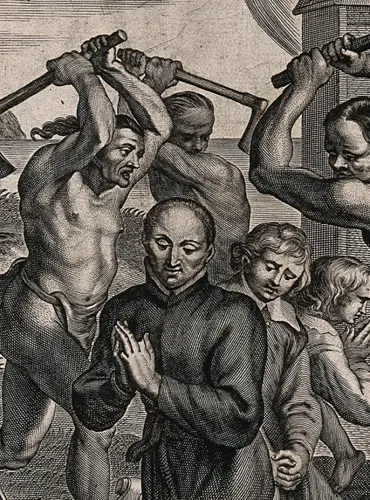

First, how beautiful! Our world is obsessed with what it thinks is beautiful, and yet it doesn’t think that that category applies to missionary work. Clearly the beauty that Paul and Isaiah mean isn’t a simple physical attractiveness: in the midst of the flames, with his eyes plucked out, his teeth cracked, his skin sliced, and his flesh roasting, John de Brebeuf was undoubtedly a missionary, but certainly was not physically good-looking. Furthermore, if we have any doubts that a missionary vocation won’t make us gorgeous, we just have to consult the nearest mirror and have those doubts removed!

Rather, both Paul and Isaiah use very specific words for beautiful, words that place the physical aspect on a secondary plane. Paul’s word is ὡραῖος (hóraios), which comes from the word hṓra, meaning, “an hour” or “the time of fulfillment”; properly speaking, then, beauty here refers to the beauty of a particular timing, or something beautiful in its timing, and therefore fruitful because it’s fully developed and in full vigor or in bloom.[2]

The missionary, then, is one who is beautiful with the beauty of God’s timing, and, because God’s timing is best, the missionary who heeds God’s timing is fully alive, in full bloom, as it were, with the vigor of His grace. The missionary lives from God’s timing.

From the world’s perspective, the North American martyrs began their work at the wrong time. If we think for a few minutes, we can easily come up with hundreds upon hundreds of reasons why, humanly speaking, their mission made no sense: for instance, they were entering into what was, for all intensively purposes, a war zone, with frequent attacks, skirmishes, and violence; they didn’t know the language, and one of the first tasks was simply to write down and decipher the grammar in order to learn it; tensions were high because of the colonists, disease, and a host of other problems, not to mention the political pressures from the different European nations; maybe if they had just waited until things settled down, when the traders had learned the language and could teach it, or the violence wasn’t so widespread, maybe then would’ve been the right time.

Yet all of these reasons ignore the one and only reason that matters, the one reason why we do anything at all, and that is, because it’s God’s will. We often sense this quite clearly at the beginning of our vocations, when we have that keen awareness that God calls “who He wants, when He wants, where He wants, and to what He wants,” but, as our missionary vocations grow and develop, we still need to conform ourselves to that will as seen in the most concrete expression of God’s love for us: His Divine Providence. This is particularly true of missionaries, who are called “children of Providence” as a badge of honor.[3] To live from Providence is to live every moment in God’s timing; in this consists the beauty of the missionary vocation, and it is here that we can “know how to blossom where we are planted,”[4] bringing the beauty of our vocation to its full vigor by the grace of the One who, “when the designated time had come, sent His Son, born of a woman,” to set us free (cf. Gal 4:4). Now, too, at our designated time, He also sends us.

In the same way, the Hebrew word Isaiah uses for “beautiful” is very uncommon; there’s only two other instances of it in the Old Testament, and in those cases it’s not usually translated as “beautiful.”[5] Properly speaking, the word means “to be at home,” and, by implication, to be pleasant or suitable, and therefore beautiful. This is the beauty we find in a place where we’re at home: even if my house is in a dump or in the ghetto, it’s still my home, it’s mine, and I’m comfortable there, and that very reason suffices for it to be beautiful.

In one sense, then, the missionary experiences the beauty of being at home wherever and whenever he proclaims the Good News since, as the bearer of eternal truth and God’s emissary, “everything belongs to you, Paul or Apollos or Cephas, or the world or life or death, or the present or the future: all belong to you, and you to Christ, and Christ to God,” as Saint Paul writes (1 Cor 3:21-23). Everything is his. Nothing that is truly human can be foreign to the missionary.

Likewise, and perhaps even more intensely, the missionary is always at home because his sight is fixed on heaven, his eternal and true home. He lives with one foot in this world, but with the other in the next; as Saint Teresa Benedicta of the Cross put it, he “walk[s] on the dirty and rough paths of this earth and yet [is] enthroned with Christ at the Father’s right hand, [he] laugh[s] and [cries] with the children of this world and ceaselessly sing[s] the praises of God with the choirs of angels.”

Writing of his captivity and solitude after Rene Goupil’s death, Isaac Jogues expresses this beautifully. During the freezing winter, he wrote:

How often in those journeys and in that lonely retreat “did we sit by the rivers of Babylon and weep, when we remembered thee, O Sion,” not only exulting in heaven, but even on earth praising thy God. How often, though in a strange land, have we sung the canticle of the Lord; and the woods and the mountains about resounded with the praises of their Creator, which never, from their creation, had they heard. How often on the stately trees of the forests did I carve the most Sacred Name of Jesus. . . . How often did I strip off the bark from those tress, and fashion on them the most holy Cross of the Lord, so that . . . through it, O Lord, my King, thou “might rule in the midst of thy enemies.”[6]

In the midst of torments, privations, sufferings, and cruelty, Isaac Jogues was beautifully at home, and indeed every missionary who truly trusts in God’s providence and sets their eyes on God alone and the vision of Him in heaven, embraces the most beautiful vocation that can be given.

Second, the feet of the missionary: it should call our attention that both Paul and Isaiah talk about the feet of the missionary. Why not the mouth, which actually proclaims the Word? Why not the hands, that perform the works of charity and make the Gospel visible? Or, even more for a missionary priest, those hands that absolve sins, that pour the waters of baptism, and that elevate the Host at Mass? Why not these?

These are important tasks, apostolic works that must be close to the heart of every missionary, and certainly every missionary priest. Yet, the ministry of a missionary is not determined or measured by these things; this is not the essence of what it means to be a missionary. The basic Old Testament word for priest is the Hebrew Kohen, formed from the verb “to stand.” Thus, the priest is “a man who stands,” and, of course, a person stands on their feet.[7]

When the priest, and we can take this broadly so as to include all missionaries, when the priest stands on his feet, he stands before two parties: before God, to beg for His mercy and for the graces the people need, and before men, as their intercessor, to ask God “to pardon what conscience dreads and to give what prayer does not dare to ask.”[8] This role as intercessor follows from his priestly consecration and from his missionary calling, and, even if the priest be unable to celebrate the sacraments or do anything else “priestly,” he remains standing, and, by standing, interceding and expiating for men, because he does these things in virtue of the indelible seal he has received.

In his book Where God Weeps, the Norbertine priest Fr. van Straaten recalls the 1964 death and funeral of Benjamin, a young Slovakian bricklayer who had been badly burned in building under construction. Remember that, at that point in time, the Church was being oppressed and suffering greatly under the Communist regime. As his coffin lay in the church, the elderly parish priest brought out his best chasuble, and lay it on the casket. It was only then that the vast majority of the villagers found out that Benjamin had secretly been a priest:

When the seminaries were closed in Czechoslovakia, Benjamin had remained true to his vocation. Released from the concentration camp, he had made his vows secretly [and] in the evening had studied under the guidance of a trolley conductor . . . a dismissed professor of theology. . . . Benjamin longed for the altar of the Lord, although he would in all probability never be able to saw Mass in a church. His aim was a priesthood on a cross without earthly advantages or honor. After he reached his goal, he never preached a sermon and never taught the catechism. Without recognition, he spent [his fifteen years] of priesthood as a bricklayer in the midst of his unfortunate people. He consoled the oppressed by nothing more than his presence, his optimism, and his encouraging word.

Reflecting on this, van Straaten writes:

Where church structures are being violently destroyed, God, who is eternally young, is creating new forms of sacerdotal life and heroism. Where the Faith is in deadly peril, it is not sufficient for Christ’s servants merely to administer the sacraments. As evidence, God has perhaps permitted that thousands of priests behind the Iron Curtain are never or seldom able to exercise their exalted function. And yet they remain priests to eternity. They must themselves become living symbols through whom God can impart His grace to souls. Is this not our duty, too? The Church will never and nowhere be destroyed as long as her priests give a clear and irresistible testimony of a life that can be lived only through Christ and in God’s strength.[9]

Indeed, the Church, as planted by the Jesuit martyrs, was never destroyed, and this is in no small part owed to their clear and irresistible testimony of a life lived through Christ and in God’s strength. In one of his last letters to a fellow Jesuit, just before setting out to return to the mission where he would die, Saint Isaac Jogues wrote of his future privations:

It will be required that I shall live among them without any freedom to pray, without Mass and [without] the Sacraments. It will happen that I shall be held responsible for all that may chance to occur between the French, the Iroquois, the Hurons, and the Algonquians . . . if any difficulty arises, but what shall I say? My hope is in God, who doesn’t need us to accomplish His designs. We must endeavor to be faithful to Him and not spoil His work by our shortcomings.[10]

Without the chance to exercise any of his usual ministries, Isaac was left, simply to stand before God and before the natives, and even now he stands, interceding in heaven. We do well to remember that this line from Isaiah appears in the same chapter, and a mere six verses, before the Song of the Suffering Servant. The one who stands on his feet to proclaim Christ does so principally through his conformity with Christ Crucified.

Lastly, who bring [the] good news: missionaries don’t simply bring themselves or preach themselves; they bring the Good News, the news that souls are worth saving. “For God so loved the world that He gave His only Son,” and not only His only-begotten One, but also thousands upon thousands of adopted sons and daughters throughout the centuries, all “so that everyone who believes in him might not perish but might have eternal life” (Jn 3:16).

Preaching the Good News means preaching not only Christ, and Him Crucified, but preaching with Him and for Him. In a letter, Saint Charles Garnier summarized what this means:

We can do absolutely nothing for the salvation of souls unless God is on our side. When we rely on him alone, through obedience, he is obliged to help us. And with Him, we accomplish all that he expects of us. On the other hand, when we ourselves choose our work, even though it be the holiest on earth, God has no obligation to give us aid. He leaves us to ourselves. And of ourselves, what can we do? Nothing at all, or—what is even worse—sin.[11]

This good news entails not only the conviction of sin (as Jogues noted, some of the natives were excited about baptism, but “flatly refused to admit that they had ever committed a sin or done any wrong”), but also of man’s great dignity, a dignity that is tarnished and lowered by sin and but renewed and raised up by Christ.[12] In the midst of their sinfulness, and all their offenses against the natural law, even cannibalism, promiscuity, infidelity, the Martyrs saw in them the potential to become great children of God.[13] Again and again, the missionary poses Saint Peter Chrysologus’s question to those he encounters: “Why, o man, are you so worthless in your own eyes, and yet so precious to God? Why render yourself such dishonor when you are honored by Him?”[14] “Why, o man, are you so worthless in your own eyes, and yet so precious to God?” Only a few years after the death of the martyrs, there would come one who was, in the eyes of her relatives, worthless, and yet very precious to God, and who allowed God to raise her to holiness. This precious child of God was Saint Kateri Tekakwitha, whose union with God was attested to by the remarkable transformation that overtook her after death: her body, ravaged, deeply scarred, and half-blinded by smallpox in her childhood, was miraculously restored to such a luminous beauty that two Frenchmen who knew her very well and who happened to stumble upon her body just after her death as it lay in the cabin, surrounded by her family, asked the priest the name “of the lovely maiden who slept there.”[15] Such transformation reveals her beauty in God’s eyes, and is a sign of the remarkable transfiguration that takes place in the soul when it gives itself to God.

Today, as we celebrate the memory of these eight Jesuits who gave their lives as missionaries in this country, let us pray, through their intercession, for the grace to always be faithful to our missionary and priestly vocations. Let us ask to for the intercession of Mary, Queen of Martyrs, whose beauty is so great that, as Saint Bernadette recounts, “to see her again one would be willing to die,”[16] she whose foot crushed the head of the serpent, and she who was the first to bring the Good News, the Word Incarnate Himself, hidden within her womb, to others.

[1] For details on this ceremony, see Rev. T. J. Mulvey’s article “The Departure of Missionaries,” in The Sacred Heart Review, Volume 21, Number 5, 28 January 1899. Most specifically, we can read about St. Theopane Vénard’s experience in Walsh, James. A Modern Martyr: Theophane Vénard (Maryknoll, NY: Catholic Foreign Mission Society of America, 1913): 78-79.

[2] For this, see Strong’s Exhaustive Concordance, Thayer’s Greek Lexicon, and Vincent’s Word Studies.

[3] Taken from a letter of Saint Theopane Vénard who wrote it to his father upon leaving for the missions; cited in Walsh, James. A Modern Martyr: Theophane Vénard (Maryknoll, NY: Catholic Foreign Mission Society of America, 1913). The whole text is worth citing: “Am I not more than ever the child of Providence? Did you not yourself give me up to God? He who watches over the birds of the air and the flowers of the field, will He not take care of me wherever I may be? I cannot help longing for you, and missing you terribly sometimes; but love suffers and is resigned, and the thoughts of Heaven grow more vivid as we become more detached from all on earth. Only a little more trust! A little more confidence in God! A little more patience! and the end will come, and the past weary years will seem as nothing; then will arrive the moment of reunion, and all will be amply compensated for and repaid, principal and interest” (48); 88.

[4] From a letter of Fr. Costantini, citing Fr. Buela, in Carlos Pereira, IVE, El Recuerdo del Justo Sirve de Bendición: Perfil biográfico del R. P. Guillermo Costantini, IVE (San Rafael: EDIVE, 2016), 62: “El Padre Buela siempre nos dice que tenemos que saber florecer en el lugar en el que fuimos plantados. Uno trató de hacer todo el bien que pudo en la corta estadía en esa hermosa tierra lojana.”

[5] The other two instances are in Psalm 93:5 מְאֹ֗ד לְבֵיתְךָ֥ נַאֲוָה־ קֹ֑דֶשׁ יְ֝הוָ֗ה (“Holiness befits your house, LORD”) and Songs 1:10 נָאו֤וּ לְחָיַ֙יִךְ֙ בַּתֹּרִ֔ים (“Your cheeks lovely [or comely] in pendants”).

[6] Francis Xavier Talbot, Saint Among Savages: The Life of Saint Isaac Jogues (San Francisco: Ignatius, 2002), 284.

[7] Cf. Carlos Buela, You are Priests Forever, vol. 1 (New York: IVEPress, 2013), 146.

[8] Roman Missal 3rd edition, Collect Prayer, Twenty-seventh Sunday in Ordinary Time.

[9] Werenfried van Straaten, Where God Weeps (San Francisco: Ignatius, 1989), 208-209.

[10] Lives of Saints with Excerpts from Their Writings, Selected and Illustrated, edited by Rev. Father Joseph Vann, O. F. M., (New York: John J. Crawley & Co., Inc., 1954) and Talbot, Saint Among Savages, 412.

[11] François Roustang, Jesuit Missionaries to North America: Spiritual Writings and Biographical Sketches (San Francisco: Ignatius, 2006), 346.

[12] Talbot, Saint Among Savages, 95.

[13] Ibid., 94.

[14] Sermo 148: PL 52, 596-598. This forms part of the office of readings for his feast day, July 30th.

[15] Cf. Margaret Bunson, Kateri Tekakwitha: Mystic of the Wilderness (Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor, 1992), 43, 121.

[16] Cf. Ann Ball, Modern Saints Vol. 1 (Charlotte, NC: TAN, 2011), 72.