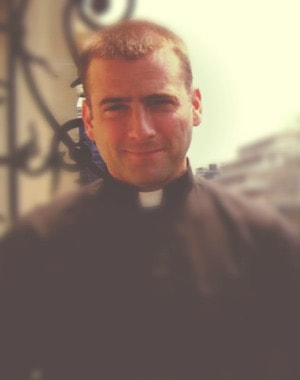

Fr. Daniel Vitz, IVE

Religious Profession: November 10th, 2007

Priestly Ordination: May 31st, 2014

Fr. Daniel Vitz was a model IVE priest who was generous in answering the call of God to serve His Church in our religious family. Shortly after ordination, he was diagnosed with a brain tumor and underwent emergency surgery. After recovering, he was able to serve as a missionary in Philadelphia, USA and Tunisia in Africa for 5 years before ending his heroic battle with cancer back in the Fulton Sheen Seminary in 2019. He courageously offered himself to go to the most dangerous mission, one where “there was a real chance of martyrdom”. Below you can find his vocation story and advice for any discerning God’s call in their life.

Content

FR. DANIEL'S VOCATION STORY

My Own Discernment

I was raised in a large, devout family—my parents had converted to Catholicism shortly after I was born, and we were raised saying the rosary and going to mass on Sunday (my parents became daily communicants when I was still quite young, but didn’t take us with them during the week). However, my Catholicism somehow never made the transition from the faith of my childhood to an informed adult faith. I went to a well-known and rather prestigious Jesuit high school on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, but the spiritual formation there was almost non-existent, and the atmosphere that pervaded it was a largely secular one. Concerned as I was about fitting in and hanging out with “cool” kids, my Catholicism took a back seat to the more pressing concerns of my budding social life, and by my junior year of high school I had firmly established myself in a pattern of behavior where my faith didn’t play much of a part in my daily life. This pattern extended beyond high school to my college years. There, inured as I was to the incompatibility between what I believed (for I did still believe) and the way I carried myself, I surrendered myself to the temporal pleasures of college life at NYU. Perhaps the most insidious aspect of this divorce between what I knew to be right and what I actually did was the fact that since my own moral position was so compromised, I rarely stood against positions that I knew to be wrong. Still, I cannot say that I ever dissented—although it was not always visible to the naked eye, my Catholic faith was an inseparable part of my identity, and I continued to accept both its teaching and its authority to teach. It is also worth noting that I was always committedly pro-life, and (perhaps more remarkable) still said the rosary, often on a daily basis—the devotion to Our Lady instilled by my mother during my childhood held me in good stead throughout those years.

Nevertheless, my faith continued to languish, and as I look back I am very aware of the restlessness that was in my soul, and can see that that I was searching in the secular world for something that I could only find in God. I moved overseas to Croatia after college, but decided to come back to New York after a year or so. I worked in Manhattan for a year, but was miserable, and knew that a simple change of jobs would not suffice. I had found myself increasingly drawn to the idea of military service, and so I decided to join the Navy. It was through the Navy that I later found myself stationed in Washington DC. I knew very few people in the DC area, and because I was working rather unusual hours, for the first time in many years I did not have the opportunity to cultivate a mind and conscience-numbing social life. Increasingly aware of my deep dissatisfaction with the emptiness of my way of life, I began a lengthy process of soul-searching and self-examination.

The beginnings of my conversion were intellectual. I remember thinking that, setting aside issues of morality or religion, it was terribly dishonest intellectually for me to believe in the truth of one viewpoint and not to act accordingly. I had avoided the charge of hypocrisy in the past by simply keeping quiet much of the time, but that was no longer acceptable to me—I had to be willing to act as a witness to what I believed. I found the idea that I couldn’t bring my actions into line with my will repellant, and treated it as a challenge to my very identity. It quickly became more than a mental exercise, however, for as I found myself with more time for thinking and reading, I began once more to pray.

I had always attended mass when I was with my family, but I had missed mass routinely when I was on my own in recent years. Now I began longing to return to the sacraments. I remember the thrill I felt at being back the first time I went to mass in Washington, and for several weeks I would go from morning mass to noon mass to evening mass on Sunday, eager to see as many different churches and liturgies as possible; I felt as though I needed to spend more time with God than one mass would allow! It was during this period that I went to confession for the first time in a long time—I had long ago forgotten the joy of a clear conscience—and it was also then that I first visited the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception. I remember being overwhelmed at the Shrine by the presence of God and by the richness—the true depth and breadth—of the Catholic faith, and deciding that I needed to go to mass during the week.

I quickly re-immersed myself in my faith, reading voraciously about Catholic history, doctrine, apologetics and spirituality, and I settled into a routine first of going to mass three or four times a week, and then of daily mass attendance. It was perhaps six months after this first renewal of my faith that it occurred to me to pray in earnest about my vocation. I realized that I’d always assumed my vocation was to marriage and family, and that I’d never really been open to the priesthood, and certainly at no point in my youth had I ever really been challenged to think and pray about it.

Like most Catholics, I had often noted the need for solid, reverent priests who were committed to living and preaching the Gospel, and who had not made their peace with the world; even before my renewal of faith I had often remarked on it. And so I decided to pray about what my vocation was. That is not to say that I ever thought that I might actually be called to the priesthood—it was really just so that I could “check that box” and in good conscience say that I had considered and prayed about the possibility. Still, I did manage to keep an open mind…

It didn’t take long. It was only shortly after my decision to begin praying about my vocation, when, while taking a walk and praying the rosary one evening, I remember falling to my knees, and thinking, “Oh no, you want me to be a priest!” The idea was gut-wrenching, and I still remember how impossible and far away it seemed to me then—I had so many obstacles built up around my heart, and God’s grace had still so far to work on me.

Soon, the self-doubts began to set in—the first of many times—as I began to rationalize the clear feelings that I had had earlier, and tried to convince myself that I was just imagining the entire thing. But God had started the ball rolling—the sensation had been too distinct for me to ignore, and I did start searching; that week I signed up for a discernment retreat with a religious order I had heard was excellent. When I have something important on my mind I like to get things done right away—the question of my vocation was weighing terribly on my heart, and I wanted to know the answer immediately.

I enjoyed the retreat, and was largely impressed with the order I visited, but felt pretty distinctly that I was not called there—a feeling that I interpreted as meaning that I was not called to the priesthood. So early on, I think I was mistaking my specific vocation with my general one—that is, I knew I was not called to the order that I had visited, and took that as meaning that I probably wasn’t called to the priesthood at all. My error was made in good faith, but it would take several more months before I realized that I had indeed been mistaken. Of course, in retrospect I should have known almost immediately—I remember getting back home from the retreat and turning on EWTN. As I started watching, I realized that the program was a newly ordained priest saying his first mass, and I almost immediately began to weep—I was rather confused by my reaction, since I am absolutely not someone who is much given to tears, and the entire experience left me somewhat unsettled. Looking back, I am very aware that God often helped me to realize where he was calling me through small, strange emotional occurrences like that one.

The most significant fruit of that first discernment retreat was a renewed sense of patience, and the realization that I had to work on God’s time, and not my own. Prior to that point, I had been almost frantic in my desire to confirm or deny my call to the priesthood, so that I could begin to order my life accordingly. I realized on the retreat that I couldn’t approach it that way—for mysterious reasons, sometimes God moves us far before we ourselves are ready, and sometimes he makes us wait when it seems unendurable to do so. I had to be listening, but it wasn’t proper to try to rush things any more than it was right to intentionally slow things down.

While I came away from the discernment retreat with the working assumption that I was not called to the priesthood but rather to marriage and family, I resolved to keep an open mind, and to continue to pray about it. I told God that if I was mistaken, and my call was truly to the priesthood, then to please send me some type of dramatic sign to let me know. I am aware that it is a fairly common phenomenon for young people discerning a vocation to the religious life to ask for this, but it is not a healthy or appropriate request, since God does not generally work that way.

In keeping with my working assumption, I went back to DC and began dating again. Still, I was unable to dismiss the idea of the priesthood. I went out over that summer with a bunch of attractive and interesting Catholic girls, but nothing really took. I’m a pretty social person, and while I had had serious girlfriends in the past and had always been comfortable on dates, I couldn’t quite get the discernment monkey off my back. It was as though as I continued praying for my discernment, I seemed to feel more and more emotionally and intellectually disconnected from the girls with whom I went out. I also started thinking a lot about the fact that although I had been dating, it had been several years since I had last had a girlfriend—the more I thought about it the stranger it seemed to me, since I’m not socially inept or dramatically unattractive—and I couldn’t help but attach some significance to it. In any case, the last straw occurred early in the fall. I asked out a very cute girl at a party, and remember thinking, “Yeah, this girl fits the bill”—she was pretty, fun, a serious Catholic, and I had quite a crush on her initially. It took about three weeks for it to just fizzle out. I remember giving her a kiss at the end of a date and thinking, “That wasn’t proper—I shouldn’t have done that”, and yet realizing that it was not an intrinsically inappropriate action—it just didn’t seem right. I don’t know if this girl sensed something of the conflict, or simply decided that she wasn’t interested in me, but either way she saved me from having to break it off. I was really in crisis at this point, but I still hadn’t received any of the dramatic signs I wanted from God in order to show me that I was called to the priesthood rather than the married life.

It was around this time that I went up to New York to visit my family, and decided to talk about my discernment with a very fine diocesan priest who is also a close family friend. I explained the whole process of my discernment and where I stood, and found myself partly hoping (though in a conflicted manner) that he would say that I did have a vocation to the priesthood—I certainly felt that the story I had explained to him was rather indicative of that calling. Still, I thought that there was one significant argument against it—I really felt like I liked girls too much! I remember being somewhat surprised when he said, “Dan, its fine if you like girls—that’s the kind of priest we need, in fact. You have to be in control of yourself, and capable of living a chaste life, but having an attraction, even a strong attraction, to women is normal, and in no way is indicative of your not having a call to the priesthood. And from what you’ve told me, it certainly sounds as though you may be called.” With that explanation, away went my best argument for not entering the seminary.

Very shortly thereafter I had to go out to San Diego for work. I was there for only three days or so, but I went to mass two or even three time a day—I felt a strong need to be in the Real Presence, praying about where God was calling me. At the time I also thought I was going to be moving to San Diego after I left Washington, and so I wanted to see the most beautiful churches out there—in particular St. Joseph’s Cathedral, the Immaculata, and the Mission San Diego.

On the second day of my trip—the feast of St. Luke the Evangelist—I was praying after mass in front of the tabernacle in the Mission San Diego when it hit me:

“Do you really need a dramatic sign? Your whole renewal of faith in the year and a half did not involve anything dramatic; it was just a realization—a firm conviction of how you had to order your life. Does the process for deciding your vocation have to be any different?”

No, I guess it doesn’t.

“So it doesn’t have to be dramatic, just definite?”

Yes.

“Okay—be a priest.”

Uh oh.

That was when I really decided I had to enter the seminary, and needed to discern precisely where I ought to go. That is not to say that I didn’t continue to have doubts—I very much did. But I noticed that when I was praying about my vocation, and particularly when I was in church, in the Real Presence, I felt quite sure about my calling to the priesthood. It was when I was out in the world—when I was out with friends or talking with a pretty girl—that I felt most conflicted about my decision. I recognized very quickly that if I were going to decide based on one of these two feelings, it obviously had to be the one I had when I was in prayer, not the one I had when I was out in a bar! I also began to realize that there while there were many things about marriage that appealed to me, there were elements that most certainly did not. I began to feel that having to work a secular job for my entire life in order to provide for my wife and family would be insufferable—I needed to be on the “front lines” for my faith. I began to feel, too, as though it would be selfish for me to focus primarily on the sanctification just of a small group of people (that is, my wife and children) when there was so much work to do. I needed to give myself to everyone.

I realized that although the decision to become a priest would entail great sacrifice, that didn’t mean that it was not a sacrifice I was called to make. Still, it really hurt when I thought about the idea of never marrying or having children. In many ways, all the joys of my vocation were hidden to me, and all I could focus on were the beautiful things that I would be giving up. I was really concerned that I wouldn’t have the courage to start or the resolve to follow through with my calling. But it hit me one day that no one is strong enough or worthy enough to be a priest—that grace can only come from God. And so I said, “Okay, God, I believe that you want me to be a priest, and I assent—I will do it. I know you know how much this hurts, and that my sacrifice is that much more meaningful to you because you know.”

Still, I asked God for help with two things. First, I said, “I am so weak—far too weak to do this on my own. I acquiesce to your mysterious plan for me, but I don’t have the strength to carry it out, so all the rest has to come from you—I am leaning on you completely and entirely.” And I remember having this amazing sense of peace, knowing that God would always make me equal to the tasks to which he was calling me as long as I could bring myself to ask. It was thrilling to realize that I wasn’t expected to—indeed couldn’t—have the strength or perseverance to do what God was asking, it was only for me to agree to do it, and then to pray!

The second thing I asked for was peace of mind—I said, “God, I believe I am called to the priesthood, but I don’t want to be a miserable priest; a martyr in my own eyes—I want to be joyful! For the next 30 days, I will make sure to spend twenty or thirty minutes each day after mass praying in your Presence. If, as I believe, you are truly calling me to the priesthood, please help me to feel at peace with my decision to enter the seminary by the end of that time.” By the end of that period I was so convinced of my calling that I could laugh about the difficulties I had had 30 days earlier!

During this period I was also reading a lot about discernment, and I came across a couple of things that really helped me to put the religious vocation into a proper perspective. The first was something written by Carter Griffin, who was a seminarian at the time for the Archdiocese of Washington, and has since been ordained to the priesthood. One of the points he made was that despite the public preoccupation with priestly celibacy, that is not what the priesthood is “about” any more than marriage is about all the other women in the world that you will not marry! In both cases the decision is really about the one love to which you do decide to dedicate your life—everything else is incidental. It hit me when reading this that the very nature of choice is such that whatever you do not choose is excluded. It is impossible to choose everything, and in most cases, it is impossible to choose more than one thing (or person). Those people who can never bring themselves to make the difficult decisions are dooming themselves to a sorry sort of life, and ultimately, a life in which their choices are made for them as a result of their indecision. Absolutely everyone is called to make hard decisions, and therefore everyone is called to sacrifice—to give up the things they do not choose. Difficult decisions will always be even more punishing if we are continually looking over our shoulders and focusing on the virtues of those things we have put aside, and that is an incredibly unhealthy approach to life. At least I had the comfort of knowing that what I had decided to sacrifice was not simply the product of my own unguided inclination, but rather something to which I felt strongly called by God—it was the right sacrifice.

The other was a piece of discernment advice written by Fr. Anthony Bannon LC, where he points out that you can’t expect that God will neuter you if he calls you to the priesthood or the religious life, because that can’t and won’t happen. Rather, you have to order your life in accordance with your call, and pray that the love and the longing that God has placed on your heart as a vocation to the religious life will be so intense that everything else will pale in comparison. I realized that I should not pray that I not feel the sacrifice that I was making by never marrying, or that the sacrifice be made easy by virtue of not finding women attractive, but that I ought rather to focus myself mentally and spiritually on my calling, and then pray for the strength to follow it through. I knew that with God’s grace it would only get easier.

So I decided that I was definitely going to enter the seminary. While I didn’t know whether it would be as a diocesan or religious priest, and therefore what seminary I would be attending, I decided at this point to make my decision public knowledge. I am a pretty open person by nature, and I’ve never been good at making a secret of the things that are weighing on my heart. Besides, there were times when not mentioning the process would have involved lying or at least elaborate evasions of the truth, and I’m not very good at being disingenuous either, so I let the cat out of the bag. I was frankly amazed—people were so intrigued by my decision, and I couldn’t get over the number of deep, sincere conversations about God and faith that I ended up having, sometimes with people I barely knew. It made me realize that I was incorrect when, early in my discernment process, I had briefly convinced myself that I would be able to do more good for the Church as a devout layman than as a priest, because people “wouldn’t listen to a priest.” The opposite was true—here I was, a layman who hadn’t even decided on what seminary he was going to enter, and already people were opening up to me about their faith in ways that I had never seen! This in not to belittle the enormous importance of the lay vocation, but I did come to realize how much I would be able to accomplish as a priest. People are naturally impressed by and drawn to self-sacrifice, and the fact that modern society is so self-indulgent only intensifies that phenomenon. When you have “put your money where your mouth is,” so to speak, people are more prepared to listen to what you have to say. It seems so simple, and patently obvious in hindsight, but I was thrilled to realize that I was going to have more wonderful opportunities to be a witness to Christ than I ever imagined.

Although my initial inclination at the start of my discernment process had been towards the religious life (as was evidenced by my decision to go on a retreat run by a religious order), I didn’t know of any solidly orthodox orders that particularly appealed to me. Confusing matters somewhat was the fact that I realized I felt very drawn to the idea of being a parish priest (for some reason, the idea of baptizing babies really struck a chord with me), although I also liked the idea of going on for a doctorate and possibly teaching. Both because of my lack of interest in the religious orders that I knew and my interest in parish work, I began to lean toward the diocesan priesthood. As part of my discernment, I decided to visit a couple of top-notch diocesan seminaries—Mount St. Mary’s in Emmittsburg, MD and St. Charles Borromeo in Philadelphia. I was somewhat apprehensive before I went, worried about what I would think of it all. I still remember sitting in on a few classes and practically laughing to myself—I was almost unable to contain my enthusiasm for the subject matter of the courses. I realized at that point that intellectually I was very much ready to begin studying for the priesthood, and that it would be a real pleasure to do so. I had known I was going to enter the seminary, but I hadn’t known that I would enjoy it so much—now I knew, and thanked God for it!

I was very impressed by the level of instruction at both seminaries, as well as with the quality and spirituality of the men studying there and their spirituality, but something didn’t quite take. I couldn’t shake the feeling that it wasn’t dramatic enough—that I would probably be living a similar life if I had just decided to get a postgraduate degree in Theology on my own. In addition, I was very aware that it was essentially a solitary vocation—although they attended mass and said the hours together every day, each seminarian largely did his own thing, just as other university students do. There was another problem as well—I didn’t know where God was calling me to serve, geographically speaking. For some reason I had a strong feeling that I was not called to the diocesan priesthood in New York—I think that perhaps I knew that I had to make a clean break from my high school and college friends. I did feel that in some important way the DC area was the birthplace of my adult faith, but I didn’t feel that either the Archdiocese of Washington or the Diocese of Arlington were obvious choices. Furthermore, every time I considered the diocesan priesthood, I couldn’t shake the feeling that my decision making process was fundamentally flawed. I was thinking about which diocese would be closest to my immediate family, which diocese had a more impressive bishop, a better presbyterate, etc. These are real-world considerations worth being aware of for a man who has already decided where his vocation lies, but they should not be the deciding factors, and deep down I knew it.

Perhaps the biggest issue was whether I would be able to live close to my family. I have always loved to travel, and lived and studied abroad at various points, but at the same time it hurt to think about being far away from my parents and siblings. I remember one day praying after mass and saying, “God, I am willing to give up everything for you”, when it struck me—“Even your family?” I knew that the answer had to be yes. I had a long conversation with my mother about this, and I remember her saying that while I didn’t have to give up my family necessarily, I had to at least be willing to give them up. I couldn’t place conditions on my vocation—my assent had to be unconditional.

I had never heard of the Institute of the Incarnate Word before it was mentioned to me in the course of a conversation with the vocations director for Arlington, who mentioned that they were an orthodox new order that often worked as parish priests, and had a seminary in Maryland. I decided to visit their seminary (The Fulton Sheen House of Formation), and was bowled over. It was a marked contrast to the spacious diocesan seminaries with their beautiful, historic chapels and campuses. Here there were about 25 seminarians and several priests living in an incredibly cramped house in a blue-collar neighborhood in Maryland, and Spanish was as likely to be spoken as English. Still, there was this amazing, palpable joy among the young guys there in that building, and it was infectious. At the recommendation of the rector of the seminary, I sat down to read the constitutions of the IVE (the standard abbreviation, which is from the Spanish “Instituto del Verbo Encarnado”). I remember going through the document and thinking, “This is it—this is exactly what I want!” I realized that I was called to life in community, and that I needed to take a vow of poverty and place myself completely in God’s hands, going anywhere in the world that he saw fit to send me. I could tell that the seminarians there felt the same zeal for their faith that I did, and had found a real joy in it. I still remember when, during my visit, I saw about twenty five framed black and white pictures of some young priests and seminarians on the wall and asking one of the IVE seminarians who they were. “The martyrs of Daimiel,” he responded. “Martyrdom. What a grace, huh?” And I recall thinking, “Yes! —Any religious order that cultivates an embrace of martyrdom like that is an order that I want to be a part of.” Finally, I loved that they had a strong focus on the intellectual apostolate without being solely an order of academics, that they had a contemplative branch as well, and that they also allowed their active members to spend time as contemplatives. There was something thrilling about the realization that my future might hold anything—perhaps I would be a parish priest in New York, or a professor at a seminary in Rome, or a monk in the Holy Land, or a martyr in Sudan. Who knew, perhaps I wouldn’t be any of those things or perhaps I’d be something else entirely—it didn’t seem to matter anymore, as long as I could be sure that it was God deciding and not me!

The parish church that the IVE seminarians used was across the street from the seminary, and had a parochial school next door. The morning after I had arrived I attended mass with all the seminarians—it was one of those wonderful clear days where the world seems “charged with the grandeur of God.” I remember walking back to the seminary after mass and stopping on the sidewalk, struck by a moment of clarity about the journey I was beginning. Across the street were parents dropping their children off at school before rushing off to work, and I was suddenly very aware of the things that those parents had given up. Never would I have to struggle through a tiresome secular job, feeling drawn away from God by the world, wondering what difference I was making and hoping to snatch a few minutes of prayer where I could, or worrying about the day-to-day difficulties of family life. By becoming a priest I would be able to devote my entire life to prayer and to the salvation of souls. It would not be easy, and certainly not free from worldly concerns, but by giving up a family for God I would also be gaining something far more beautiful in my eyes. My life would indeed be a joy, and it was those men who had embraced family life that were making the real sacrifice. It was then that I knew that I had really been given the grace to love my vocation. I haven’t even begun the seminary, but I know now that I want to choose the better part, and thanks be to God for that.

“God, I believe I am called to the priesthood, but I don’t want to be a miserable priest; a martyr in my own eyes—

Fr. Daniel Vitz, IVE

Necessary Stages for Discernment (says Me)

Fr. Daniel's advice on the stages of discernment.

I have been thinking over common, recurring themes from my own and others’ vocational discernment–in part prompted by the questions of people whom I know who are themselves discerning a call to the religious life. For instance, I have encountered folks who say, “I feel as though I am probably called to be a priest, but don’t love the idea of the priestly vocation, and feel as though I ought to if I am indeed called there.” It’s normal that folks feel as though they ought to love the vocation to which they feel called, but its odd when you consider that most have never really even accepted the call, much less embraced it! Of course they don’t love it. Also, many times people haven’t even decided what diocese or order they would enter—how can you love something that you haven’t even gotten to know? It’s like wanting to love a hypothetical woman without having met her—or in many cases, without ever having met a woman at all!

Stage One:

Openness to your Calling

This is in a fundamental sense about our own will, and I think that is where most vocations to the religious life die. Each of us must keep at the forefront of our understanding the fact that God calls each of us in disparate ways, and that he may be calling us to an unexpected place. We have the obligation to be open to whatever that call is, and therefore must attempt to keep our minds open and ensure that our prayer life reflects that openness. That is, we must pray about our vocation and be genuinely listening–time spent in the Real Presence is crucial.

Stage Two:

Understanding your Calling

This ultimately has to come from God. One of the crucial things here is to keep in mind the fact that God doesn’t tell us outright (except for a lucky few), but rather works on our hearts in varied and mysterious ways. The only point I would like to make is that God wants you to ask for his guidance, but he doesn’t want to hide your vocation from you! If you are trying to keep an open mind and find yourself drawn or pointed again and again towards one place–particularly when you are in prayer–that’s a sign. The same thing goes (except more so) for when you find yourself unable to remain unbiased, and still find yourself pointed toward that which you do not want for yourself! Also, if you are feeling really unsure, I would recommend visiting a seminary or religious house—after all, how can you know if you will or won’t like something if you have no idea what its like?

Stage Three:

Acceptance of your Calling

This ultimately has to come from God. One of the crucial things here is to keep in mind the fact that God doesn’t tell us outright (except for a lucky few), but rather works on our hearts in varied and mysterious ways. The only point I would like to make is that God wants you to ask for his guidance, but he doesn’t want to hide your vocation from you! If you are trying to keep an open mind and find yourself drawn or pointed again and again towards one place–particularly when you are in prayer–that’s a sign. The same thing goes (except more so) for when you find yourself unable to remain unbiased, and still find yourself pointed toward that which you do not want for yourself! Also, if you are feeling really unsure, I would recommend visiting a seminary or religious house—after all, how can you know if you will or won’t like something if you have no idea what its like?

Stage Four:

Embrace of your Calling

This too requires the active participation of the individual will. It is possible to accept your vocation without making the necessary efforts to love it, and it will make you miserable. Therefore, you have to embrace every aspect of your calling, and ask God for the grace and the strength to love it in its entirety. I sometimes think that priests who leave the priesthood do so not only because they fail to work at maintaining their love for their vocation, but also because they never embraced everything about it (for example, believing that a relaxation of the discipline of clerical celibacy was inevitable, they failed to internalize and love their life of chastity). Remember that agape, the highest form of love, requires the act of will–in order to love the particular relationship with Christ that we have in our vocation, we need to earnestly desire it.

Stage Five:

Love of your Calling

This is a gift from God. Fortunately, since God wants us to go to Heaven, he has called us to do what is best for our souls, and what will ultimately make us happiest. If you are genuinely called to the religious life, and have embraced your vocation heart and soul, God will give you the grace to love it absolutely. This stage is where you want to remain for the rest of your life, and perhaps if you feel as though you’re not there anymore, its because you’ve fallen into a place where you need to work again at Stage Four.

There’s a lot of discussion about how much the Church needs priests and religious, and I think we can all see that. But it’s a mistake to talk about a “vocations crisis”—because that implies that there aren’t enough vocations to the priesthood. But Christ told us that he would never leave his Church without shepherds, and so he is definitely still calling many, many young men to the priesthood, and he calls many, many young women to the religious life. The crisis is not in the number of men and women who God calls, the crisis is in the tiny percentage of those young men and women who actually respond to that call. That’s the crisis.