Monday of the Twenty-ninth Week in Ordinary Time – Lk 12:13-21

In today’s Gospel, Jesus not only warns us about the dangers of greed, but also explains to us the need to trust in God. The Gospel narrative begins with a request that Jesus intervene in a family dispute; historically, rabbis were supposed to help resolve legal disputes, so the request isn’t out of place. Nevertheless, Jesus doesn’t answer the man directly, instead replying: “Friend, who appointed me as your judge and arbitrator?” A more literal translation would be, “Man, who appointed me judge or arbitrator over you two?” The question is a pointed one, and gets to the root of the problem: Jesus, of course, has “all authority in heaven and on earth,” yet, if these men are fighting over the goods of this world, they show that that’s what they think is most important. They really haven’t accepted Jesus’ authority because they’ve set material goods in the center of their hearts and on Christ’s throne. Jesus has authority over them, but they refuse to accept it.

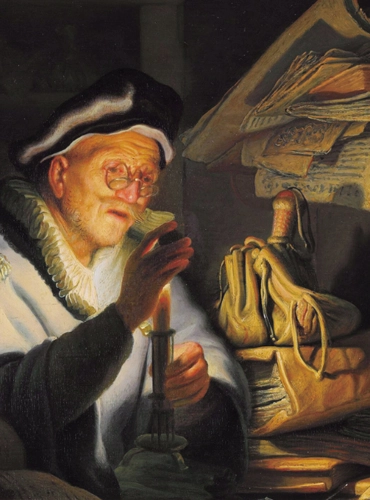

Jesus follows this up with a parable, and we need to understand a little bit of the historical context. In Biblical times and literature, barns “symbolize an accumulation of wealth; they are the best attempt humans make to survive, control, and master their world. . . . When Jesus uses these examples, it is primarily to contrast human security with divine provision,” that is, with trust that God will provide.

Only the rich and the well-to-done can have barns; those who are struggling to make a living can’t store up anything. The rich man in the parable already had barns: in other words, he was already doing just fine financially. Rather than use that extra wealth to help the poor or to provide for the needy, he decided just to hold on to it and keep them for himself. Perhaps no other parable is as filled with greed as this one: the rich man uses eleven personal pronouns in three verses. Those goods could have helped him get to heaven; instead, he decides to hoard even more. He stored up treasure for himself, says Jesus, but wasn’t rich in what mattered to God. The word used to describe him, “You fool,” literally means “one without perspective,” one who can’t act well because he doesn’t see things rightly.

What does matter to God? On one hand, it’s to use the things that we’ve been given, whether that’s money, talents, a good reputation, anything, to help bring others to God. On the other hand, instead of trusting in ourselves and what we can store up, it means trusting that God will look after us; we don’t need to trust in things for security.

Notice that in the Bible, we never call God the “Divine Mathematician,” and aside from the specific measurements for things like the Ark and the temple (which, it should be noted, were not standard measurements, since they were things like the length of an arm, or the span of a palm), God doesn’t do much insisting on numbers. David was punished for taking a census, because he was trying to place his trust in numbers and statistics. On the other hand, in the book of Judges [7:1-25] Gideon started out with 32,000 soldiers, and yet God kept sending them home until with 300 Gideon defeated the enemies of Israel. The divine economy is far different from the human one, and it means that even if we think that we don’t have the capacity to become great saints, if we trust in God, rather than in ourselves and in things, we really can become great saints, if only we put our trust in Him. We can ask ourselves: do I put my trust in things rather than in God? How much do I really trust in Him?

Today, let us ask for the grace, through the intercession of Mary, Queen of Heaven and Earth, to free ourselves from the chains that keep us bound to things, so that we can become rich in the things that matter to God.