[1] We follow J. Holzner, El mundo de San Pablo; Madrid – México – Pamplona 1965, 277322.

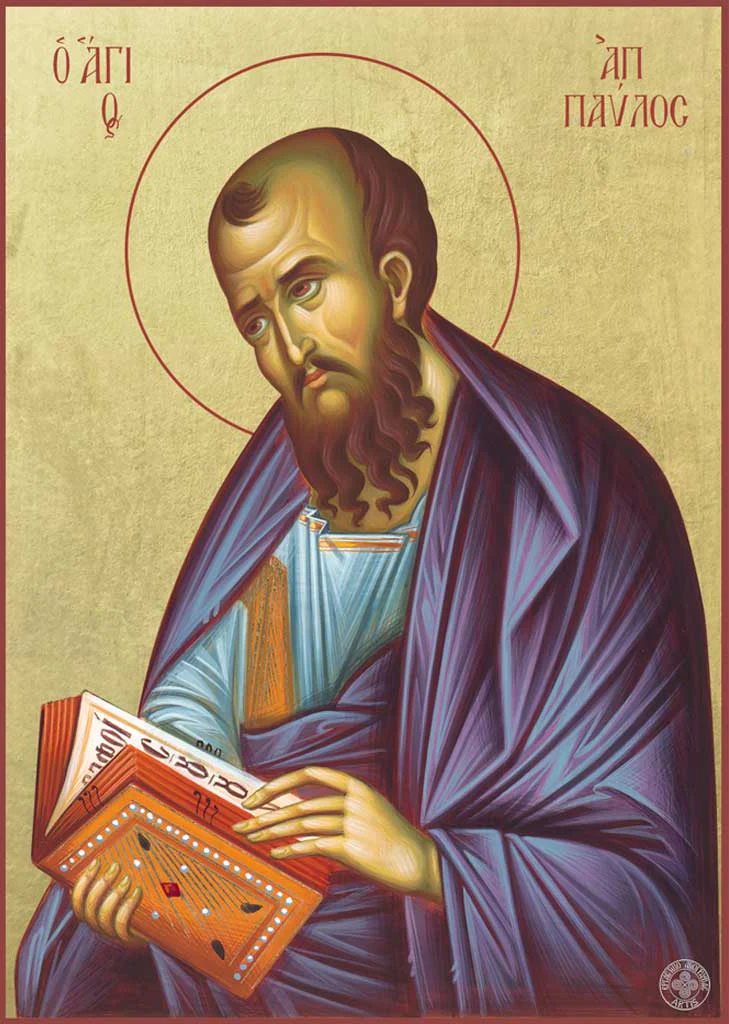

When we contemplate Saint Paul as a priest, we should not think that we are examining simply one aspect of his person or something ornamental to him. On the contrary, we are dealing with the most profound element we can see in him. From what ever angle we might observe Saint Paul, be it as a thinker or as an orator, as a pilgrim Apostle and missionary or as a mystic, as a founder and organizer of religious communities, in all of these, the secret fire and hidden source of his activity is always the same: Saint Paul, the priest. He is a priest, and thus his entire being, through and through, has something sacred, immersed, as it were, in the divine sphere.

Upon considering Saint Paul the priest we are, first of all, re ferring to the man who surrendered himself without reserve to God, to Christ, to the Spouse of Christ, and to the soul of his neighbor; it is a surrender that, at the proper time, is a surrender of his spirit, his heart, his will, his body, and of his entire person ality down to his last fibers. Everything is holiness in him; he is a man in whom the consecration of his spirit and body left has no place untouched. Not just any part of his being was consecrated, as though he thought and felt in a worldly way, like other men. Saint Paul had no area of personal interests; he is a man of holy A.

The “Man of God”

Saint Paul teaches us what he understands to be proper to the priest by using the expression (ánthropos theoú), that is, man of God. He employs this phrase twice in the letters to Timothy; he uses it once to remind Timothy of his state as a priest: But you, man of God, avoid all this. Instead, pursue righteousness, devotion, faith, love, patience, and gentleness. Compete well for the faith. Lay hold of eternal life, to which you were called when you made the noble confession in the presence of many witnesses (1 Tim 6:1112). The other is: All scripture is inspired by God and is useful for teaching, for refutation, for correction, and for training in righteousness, so that one who belongs to God may be competent, equipped for every good work (2 Tim 3:1617). This expression designates the priestly character that is formed under the guidance of the teachings of Sacred Scripture, in which the man of God learns that he must make himself like Christ in His Passion and in the persecutions He suffered.

According to H. Windisch,[1] in ancient times there was a doctrine of (theios) and a tradition of theios. Following the teachings of Plato, the Stoics, and the Cynics, there was a type of the supreme human: that of the divine man who contained within himself the necessary condition for being a priest, namely, being (haguíos), that is, pure in the religious sense.

This type of man:

- avoids sinning against God

- knows the substance of sacrifice

- has a profound and sacred knowledge of God

- on account of his priestly personality, he earns a reputation from all of his deeds

- in his relations with his neighbor, he is like an angel or messenger of Zeus, sent to earth in order to dissuade men from evil and divine radicalism.

- and, as a friend of God, he sees the world as a battlefield, where he must fulfill his mission for humanity: as Apollonius said of him, “men are his sons, women his daughters, and he is concerned for the entire world.”

Antiquity concocted certain “theios figures” related to this doctrine of theios, figures in whom they felt this ideal had been fulfilled. Figures of this character included Pythagoras, Empedocles, Menceles, Socrates, Chrysippus, Epictetus, and Apollonius of Tyana. Later on, during the era of decadence, this concept became broadened even more so as to include certain rulers, like Alexander, Pompey, and Augustus. Aristotle passes onto us a secret archaic doctrine, which states that there are two classes of men: common, mortal men, and men of the type of Pythagoras.

Antiquity imagined, intuited, and desired the kingdom of the numen or the sphere of the divinity in this way, because the world was attracted to a man who had a true priestly character; antiquity was propelled by a desire for this man, another manifestation of what the world feels for its Savior and its desire to be redeemed. It was in this setting, thoroughly pierced by religious sentiments, that Jesus Christ, in the fullness of time, made His appearance, bringing a superabundant fulfillment to all of the hopes and desires of the human heart. Following after Him (keeping in mind that there can be a great difference between teacher and student), the greatest of His disciples, the one of the strongest spirit, was Saint Paul.

When Saint Paul walked among the Greeks, he entered into a world that already had an idea of the theios, a world that thought that the idea had been fulfilled in a series of figures, some authentic, and others false. His contemporaries, both believers and pagans, perceived something sacred, something holy, something Divine, in Paul, either accepting him with veneration and enthusiastic love, or rejecting him with passionate hatred.

Let us recall, for example, the scene in the garden of Sergius Paulus, the encounter with Elymas the magician, and the impression this scene gave the former: When they arrived in Salamis, they proclaimed the word of God in the Jewish synagogues. They had John also as their assistant. When they had traveled through the whole island as far as Paphos, they met a magician named BarJesus who was a Jewish false prophet. He was with the proconsul Sergius Paulus, a man of intelligence, who had summoned Barnabas and Saul and wanted to hear the word of God. But Elymas the magician (for that is what his name means) opposed them in an attempt to turn the proconsul away from the faith. But Saul, also known as Paul, filled with the holy Spirit, looked intently at him and said, “You son of the devil, you enemy of all that is right, full of every sort of deceit and fraud. Will you not stop twisting the straight paths of (the) Lord? Even now the hand of the Lord is upon you. You will be blind, and unable to see the sun for a time.” Immediately a dark mist fell upon him, and he went about seeking people to lead him by the hand. When the proconsul saw what had happened, he came to believe, for he was astonished by the teaching about the Lord (Acts 13:612).

Let us think also of the scene in Lystra, in which people thought they were experiencing a theophany: At Lystra there was a crippled man, lame from birth, who had never walked. He listened to Paul speaking, who looked intently at him, saw that he had the faith to be healed, and called out in a loud voice, “Stand up straight on your feet.” He jumped up and began to walk about. When the crowds saw what Paul had done, they cried out in Lycaonian, “The gods have come down to us in human form.” They called Barnabas ‘Zeus’ and Paul ‘Hermes,’ because he was the chief speaker (Acts 14:812). Or, we can think of the scene in Philippi, when they were followed by a girl who told fortunes, exclaiming, “These are slaves of the Most High God”: As we were going to the place of prayer, we met a slave girl with an oracular spirit, who used to bring a large profit to her owners through her fortunetelling. She began to follow Paul and us, shouting, “These people are slaves of the Most High God, who proclaim to you a way of salvation.” She did this for many days. Paul became annoyed, turned, and said to the spirit, “I command you in the name of Jesus Christ to come out of her.” Then it came out at that moment.

We can think of the jailer of the prison in that last city, who believed that the two strangers were theoi and that they had caused the earthquake as a divine phenomenon: About midnight, while Paul and Silas were praying and singing hymns to God as the prisoners listened, there was suddenly such a severe earthquake that the foundations of the jail shook; all the doors flew open, and the chains of all were pulled loose. When the jailer woke up and saw the prison doors wide open, he drew (his) sword and was about to kill himself, thinking that the prisoners had escaped. But Paul shouted out in a loud voice, “Do no harm to yourself; we are all here.” He asked for a light and rushed in and, trembling with fear, he fell down before Paul and Silas. Then he brought them out and said, “Sirs, what must I do to be saved?” And they said, “Believe in the Lord Jesus and you and your household will be saved.” So they spoke the word of the Lord to him and to everyone in his house. He took them in at that hour of the night and bathed their wounds; then he and all his family were baptized at once. He brought them up into his house and provided a meal and with his household rejoiced at having come to faith in God (Acts 16:2534).

Let us bring to mind the Galatians, who took Paul for an angel instead of a man: you did not show disdain or contempt because of the trial caused you by my physical condition, but rather you received me as an angel of God, as Christ Jesus (Gal 4:14). This happened in the Agora in Athens as well, where the philosophers took him for a messenger of strange gods: Even some of the Epicurean and Stoic philosophers engaged him in discussion. Some asked, “What is this scavenger trying to say?” Others said, “He sounds like a promoter of foreign deities,” because he was preaching about ‘Jesus’ and ‘Resurrection’ (Acts 17:18). We can think of a parallel scene in the Gospels where the leper falls prostrate in front of Jesus: And then a leper approached, did him homage, and said, “Lord, if you wish, you can make me clean.” He stretched out his hand, touched him, and said, “I will do it. Be made clean.” His leprosy was cleansed immediately (Mt 8:23); this is the proskynesis3 of the Gentile in the face of the theios; or, as the other centurion exclaimed at the foot of the cross: Truly, this was the Son of God! (Mt 27:54)[2]. Yet again we find that sense of the divine.

What the human heart has always desired, although no one would have imagined it from such diffuse and superstitious concepts as the theios supposes, has been incorporated into the Christian idea of the man of God, that is, of the priest. The priest is a man with knowledge of the sacred and the divine, the theologian, the announcer, the mystagogue who introduces us to the sacred mysteries, the one who cleans men from their faults and changes them into creatures of God.

B. The Essentials

According to Saint Paul, however, what is essential to the Christian priesthood is something very particular: a certain vocation, a being called to participate in the high priestly functions of Christ; it is a possession, in a certain measure, of the spirit of Christ and, along with that spirit, a very particular communion of life and of suffering with the Lord. All of this we usually summarize in the expression sacerdos alter Christus, that is, the priest is another Christ. Paul understands the very depths of this central idea of the priesthood as presented in the New Testament: God has claimed him for His service, even from his mother’s lap. Christ has taken him, anointing him with the Holy Spirit, on account of which Paul is a servant, a messenger, and a keeper of secrets, the support of the Gospel. He finds himself armed with special strengths that permit him to overcome even demons. He maintains a continuous connection of life and of suffering with Christ, feeling in his pains those of Christ Himself.

Saint Paul received his priestly vocation directly from God; he examines human existence down to its last little cracks, in the light of his ideas and of the loving designs of God. At every moment he feels surrounded by the divine idea of love; he also feels called to be very close to the Son, and to become His herald.

C. When Was He Ordained a Priest?

If we ask ourselves when and by whom Saint Paul’s priestly ordination was conferred, we can answer that it took place during the episode of Damascus, in the same way that the Apostles were anointed by the Holy Spirit at the Last Supper. Jesus Christ is not subject to any sacrament, as He was anointed High Priest by the Holy Spirit through His Incarnation. Saint Paul defends himself tooth and nail with subordination, which is shown by the fact that he considers himself as a secondclass apostle, belonging to a second generation, and insists that he owed neither his Gospel nor his vocation to the old Apostles, but rather received them directly from Christ. This is because he is firmly convinced that his powers, functions, and the dignity and representation of the priestly office were virtually contained in the vision through which he first felt his vocational calling.

We cannot, of course, reduce everything that takes place in Saint Paul’s to what happened in Damascus, but certainly that event constitutes a starting point, and the initial spark of his apostolic ministry. Everything that comes afterwards comes from the seed planted in that event.

Today, the Church needs exceptional missionaries who, by living the very life of Christ and by falling completely in love with Him, might feel in the depths of their souls what Saint Paul lived and felt, that intense calling: woe to me if I do not preach the Gospel (1 Cor 9:16).

May the Blessed Virgin Mary obtain this grace for us.

[1] Cf. H. Windisch, Paulus and Christus, Leipzig 1934.

[2] Proskynesis, from Greek προσκύνησις, from the words πρός (pros) and κυνέω (kuneo), literally meaning kissing towards, refers to the traditional Persian act of prostrating oneself before a person of higher social rank.